Introduction

Every new year starts the same way: big health goals and even bigger motivation. Eat better. Lose Weight. Cut back on sugar. Feel more energized.

But a few weeks or months later, many of these goals quietly fall away. Research consistently shows that most New year's health resolutions don't make it past the early part of the year. And that reveals an important truth: motivation can start change, but it doesn't sustain it.

Behavioral nutrition research points to the first 90 days as critical window-when intentions turn into daily actions and early routines begin to take shape (Spencer at al., 2007). What happens during this period can determine whether a goal fades or becomes a lasting habit, especially when supported by evidence-based strategies (Ashton et al., 2019).

What Science Tells Us About Nutrition Behavior Change

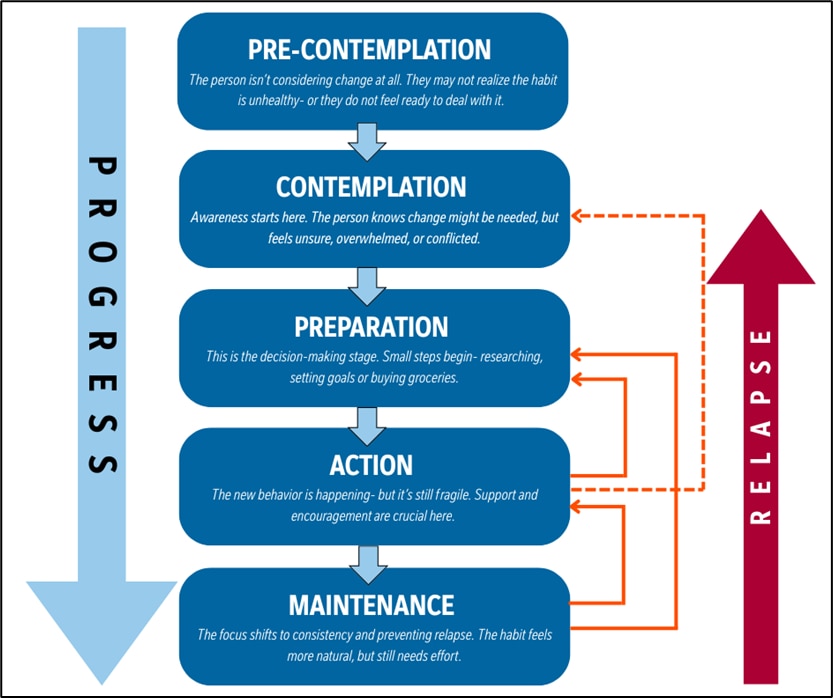

Behavior change is a process, not a single decision. Nutrition behavior change is best understood as a progressive and dynamic process, rather than a one-time choice. The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) describes behavior change as movement through five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance (Spencer et al., 2007).

Behavior change is a dynamic process where individuals progress through stages but may also relapse, particularly from action or maintenance. Relapse is common and offers opportunities for learning and development.

This framework is especially relevant for New Year health goals, as many people start January motivated but may regress due to a lack of skills, planning, or support when facing real-life barriers. Thus, Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs) are crucial, beyond just education alone.

Among the most effective techniques are:

- Goal setting and action planning

- Self-monitoring of dietary behaviors

- Feedback and reflection

- Problem-solving and barrier identification

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that interventions incorporating these techniques led to greater improvements in dietary intake compared to information-only approaches (Ashton et al., 2019). These strategies increase self-efficacy, a key predictor of long-term adherence.

The First 90 Days: A Practical Evidence-Based Framework

Days 1–30: Building Awareness and Readiness

The first month focuses on clarifying goals and building awareness. During this phase, individuals benefit from assessing their current eating patterns and identifying small, achievable changes rather than attempting drastic dietary overhauls

According to the TTM, strategies such as consciousness-raising and self-evaluation are most effective during this stage (Spencer et al., 2007). Education should emphasize practical understanding, such as recognizing portion sizes, identifying frequent sources of sugar or sodium, and understanding meal patterns.

Example of an evidence-aligned goal:

“Increase vegetable intake to at least two servings per day” rather than “eat clean.”

Days 31–60: Action and Skill Development

During the second month, individuals actively implement dietary changes and begin forming routines. This phase requires consistency, monitoring, and adjustment.

Self-monitoring—such as using food logs or simple checklists—plays a central role during this stage. Evidence shows that individuals who monitor their behaviors are more likely to sustain dietary changes, particularly when monitoring is paired with reflection or feedback (Ashton et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020).

Barriers often emerge during this period, including time constraints, food access, social eating, or fatigue. Addressing these challenges through problem-solving helps prevent early dropout.

Example of an evidence-aligned goal:

“Eat 2 servings of vegetables most days if the week (5-6 days) and keep track of consumption through tracker or meal planner”

Notice that the goal is not higher yet- its more consistent. You stop trying and start planning.

Having a meal planner will definitely help you out. Try this Meal Planner from Nestle Goodnes PH: Create your Weekly Menu Planner | Nestlé Goodnes PH

Days 61–90: Early Maintenance and Habit Strengthening

By the third month, successful behaviors begin to feel more familiar, but consistency remains fragile. This phase focuses on reinforcing habits, strengthening confidence, and preventing relapse.

Research suggests that flexible, adaptive approaches—rather than rigid dietary rules—support better long-term adherence (Spencer et al., 2007). Celebrating small successes and revisiting personal motivations help sustain engagement as behaviors transition toward maintenance

Even on busy days, incorporating vegetables into meals is achievable by adding quick options like chopped greens to rice or a small side salad with dinner, reinforcing healthy habits and demonstrating that nutritious eating fits into a hectic lifestyle. For easy vegetable additions, consider trying the Egg Salad Recipe | MAGGI® | Nestlé Goodnes PH or the Cucumber Salad Shake | Nestlé Goodnes as convenient snack options or side dishes for dinner. For more recipe inspiration, please visit the Nestlé Goodness PH website.

| Why New Year Health Goals Fail | What Works Based on Evidence |

|---|---|

|

|

For dietitians and nutrition professionals, the first 90 days of a client’s behavior change journey offer a strategic opportunity to move beyond education and into meaningful habit formation. Evidence consistently shows that knowledge alone rarely leads to sustained dietary change; rather how nutrition guidance is delivered and supported determines long-terms success (Ashton et. Al, 2019)

Dietitians can follow the 90-day structure to guide follow-up sessions:

By anchoring counseling strategies in behavior-change science, dietitians play a critical role in helping clients transform short-term New Year intentions into sustainable nutrition habits.

Rather than relying on willpower alone, evidence suggests that structured, realistic, and culturally appropriate strategies offer the strongest foundation for long-term success.

Nestlé

Nestlé

No comments here yet.